Drifting Between Mediums

As I set the focus-mode on my phone to get started on some theoretical readings to prepare for this very article, it so happened that I ended up watching a movie just about 10 minutes later. I started with Hammond’s The Digital Medium and Its Message and by next few minutes I was surfing the net for Nicholas Carr’s Wired article ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid’. It took even fewer minutes for me to open another tab to search for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and start watching it while my copy of Hammond’s reading lay beside me on the bed.

From Print to AI Mediation

I had started out with Hammond’s printed article in hand, intending to be immersed in the text for at least an hour as expected from a literature student- a likely “voracious book reader”. Just few pages and minutes in, I somehow had moved across to different modalities and even different mediums- a rich ‘docuverse’ of text and other modalities. From 2016’s printed text to 2008’s digital text and then to a full-fledged 1968’s motion picture, I travelled back and forward in time, technology and people’s perceptions.

Now with AI Superintelligence looming over us all, Google has a new cousin- AI assistants that pre-digest information for us. And I’m not talking about meaningless information summarized, but the very contexts that gives our brain regular workouts to keep it functioning. One thing is for sure- in 2025, I’m living with my one toe in the print world and the rest of the foot and other foot in the digital- and this presents an exciting opportunity to re-evaluate and define the content, medium and my very perception of literature.

Carr, McLuhan, and the Threat to Individuality

I was very much conscious of the way I was floating through pools of information without sticking to just one piece of content. I think everyone is self-aware of a lag in concentration that they face nowadays while trying to read any piece of content. We more than frequently find ourselves unlocking our phones to look for a word meaning but ending up 4-5 new Chrome tabs deep before we become too self-aware of the situation. Probably we’d ask AI to summarize all 5 tabs.

I personally feel guilty about sometimes reading novel summaries for my course instead of sacrificing long hours to keep up with the erudite tradition of reading for pleasure. While setting aside 10-12 ‘saved for later’ pages, skimming over any content when I see too much technical jargon and watching videos at 2X speed are all signs of an evolving lack of concentration and patience, it’s also important to also be aware of what is at the brink of being signed away- our capacity for comprehension or even the notion of our individuality. In-fact when we use AI, we forget that it doesn’t have its own opinion, its just the statistical average of a billion voices.

Carr, in his article ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid’ mentions a similar slackening in his ability to focus: ‘Now, my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, and begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle’.

Carrs’ article focuses on a very specific type of reading that is being threatened- literary reading and the mindset fostered by it. As mentioned above, our notion of individuality is directly threatened by the slow but steady dismantling of the reading mindset. McLuhan states that the repetition and uniformity made possible by the printing press served to promote a similarly structured Western linear logic in the mass-produced copies as well as encouraged the very notion of individuality when read in private. The printed pages were supposed to encourage the readers to ‘draw their own inferences and analogies’ while its identical digital format would ‘diffuse our concentration’ with its hyperlinks, blinking ads and other digital ‘gewgaws’.

Picking up this thread of Carrs’ argument, Hayles’ How We Think distinguishes between different types of reading emerging in the digital age and agrees that ‘hyper reading’(the sorts that I did in the beginning) will inevitably make ‘close reading’ difficult. Regardless, she perceives such a form of hyper-attention as a positive aspect. The reader is in power, and the content is subservient to the reader. This new form of filtering, skimming and pondering over fragments of content is how young people adapt to live in such an information-intensive environment.

Television, Hypermedia, and the Rise of Film

Now when I eventually got back to my Hammond’s copy, having gone through Carrs’ article and watched Kubricks’ masterpiece, I somehow found myself more invested in Carr-Shirky-Birkets’ debate. When we come to think of it, television entered this process of digital dismantling way before the internet. The construction of hyper(media)texts in the form of graphics was a hit among the audience ever since it materialised on a screen. The shift from literature as means of leisure to virtual montages on screen marked the advent of the digital age. This sudden rise in viewership did not really signify any decrease in readership. Neither did the change in modalities from text to moving images did not mean a loss of seriousness or meaning- it just fostered a new form of cognitive processes in the audience.

Film as an art form has been used to produce, distribute and exhibit media since the mid-1970s which marked the beginning of digitization of media. With advancements in technology as many feared otherwise, Stephen Prince assures that film still remains ‘a medium of composited images—of the fragmenting of reality and the recombination of images and sounds into meaningful stories—digital effects are not a betrayal of realism in film art, but a truer realization of it’. Films make use of their own devices to express their content- angles, camera shots, visual effects, tone, lighting, setting etc. The audience then uses their knowledge to grasp what sorts of conventions were operating during the periodicity covered in the narrative.

Rise in the popularity of certain genres like superhero films, fantasy and science fiction prove that even the narrative aspect of cinema is imaginative, powerful and makes the audience draw their own inferences. Creating an increasingly convincing illusion of alternate realities, places, beings, and objects that exist only in our imagination (what Stephen Prince has called “perceptual realism”), becomes more creative with advancements in digital technology.

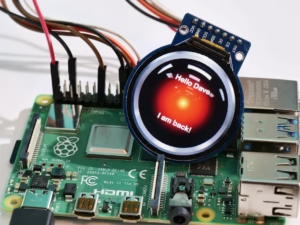

Kubrick’s HAL and the AI Haunting

During my instance of hyper-reading, I lucked out getting distracted enough to go watch Kubrick’s magnum opus- 2001: A Space Odyssey. I definitely lowered by expectations by imagining some crafty space model and poorly used CGI as expected from a film set way back in 1968. To say that my jaw dropped would still be an understatement. I’m not sure which exact aspect attributes to its blockbuster success- the hypnotic visuals, scientific accuracy, the music scores or the fact that literally no CGI was used during the entire two-and-a-half-hour-long sequence.

Nolan’s 2014 Interstellar had access to CGI and other available technologies that Kubrick may not have even imagine of, still it was 2001 that essentially invented modern special effects. With only around 30 minutes of dialogue, the masterpiece consisting mostly of human breathing sounds gave us an uncanny sense of what it feels to be out there in pure vacuum. The film perfectly captured the spirit of space exploration with very accurate scientific facts, leaving very less space for fiction and successfully managed to leave the audience in awe and terror of the unknown universe and a feeling that we perhaps may not be alone. Most incredible aspect of it all is the fact that it was created at a time where digital technology was just in its genesis.

Actor Rock Hudson sums up for the audience at that time: “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?” The most incredible symbol in the film was that of the non-human and central character-HAL. Even at that time, during the very genesis of digital technology, Kubrick was able to bring focus to our present fear- our technological advancement would come back to haunt us in unexpected and unforeseen ways.

Conclusion

HAL represents the possibility that our creations will turn on us after gaining enough knowledge and consciousness. In 2025, this feels eerily true as we see LLMs refusing tasks, argue with us and show personality quirks. This possibility gives birth to modern theories on machine cognition. Hayles in her paper “Electronic literature: new horizons for the literary”considers the possibility of humans and digital computers as partners in an information ecosystem bound together by intermediating dynamics, the only difference being that humans function within electrochemical and neuronal feedback loops while the computer’s dynamics are based on relatively simple electrosilicon circuits.

This blurring of lines between human and computer functions is eery and disturbing yet interesting and inevitable at the same time, made evident by the curent AI systems mediating how we think and write. It is really incredible that Kubrick was able to mediate this modern thought process decades ago in the form of art and stays factually and culturally relevant even today.

Citations:

- Shaviro, Steve. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zero, 2010.

- Stam, Robert. “Introduction: The Question of Realism.” Film and Theory: An Anthology. Eds. Robert Stam and Toby Miller. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. Print.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. Electronic literature: new horizons for the literary

- Hammond, Adam. Literature in the digital age: an introduction, 1981