Aging and the Senescent Cell Dilemma

When a sink overflows, it’s often due to a blocked drain. Similarly, as we age, senescent cells—non-dividing “zombie” cells—accumulate in body tissues, flooding our systems. These cells, instead of dying as they should, remain active and contribute to chronic inflammation and age-related diseases. Research indicates that removing these cells could reduce inflammation, delay diseases, and even extend lifespan. Yet, despite this potential, no effective drug directly targets senescent cells.

A team at the Weizmann Institute of Science, however, offers a new solution. In a study published in Nature Cell Biology, they reveal that senescent cells evade removal by clogging the immune system, preventing it from functioning properly. By using innovative immunotherapy—similar to revolutionary cancer treatments—they demonstrated how to remove these cells in mice, opening new doors for treating age-related diseases.

How Senescent Cells Evade Immune Detection

Led by Prof. Valery Krizhanovsky and colleagues, the Weizmann team has long studied how senescent cells contribute to aging and chronic inflammation. Collaborating with Prof. Uri Alon, their earlier mathematical models predicted that young bodies remove senescent cells in days, while older bodies struggle as these cells delay their own elimination.

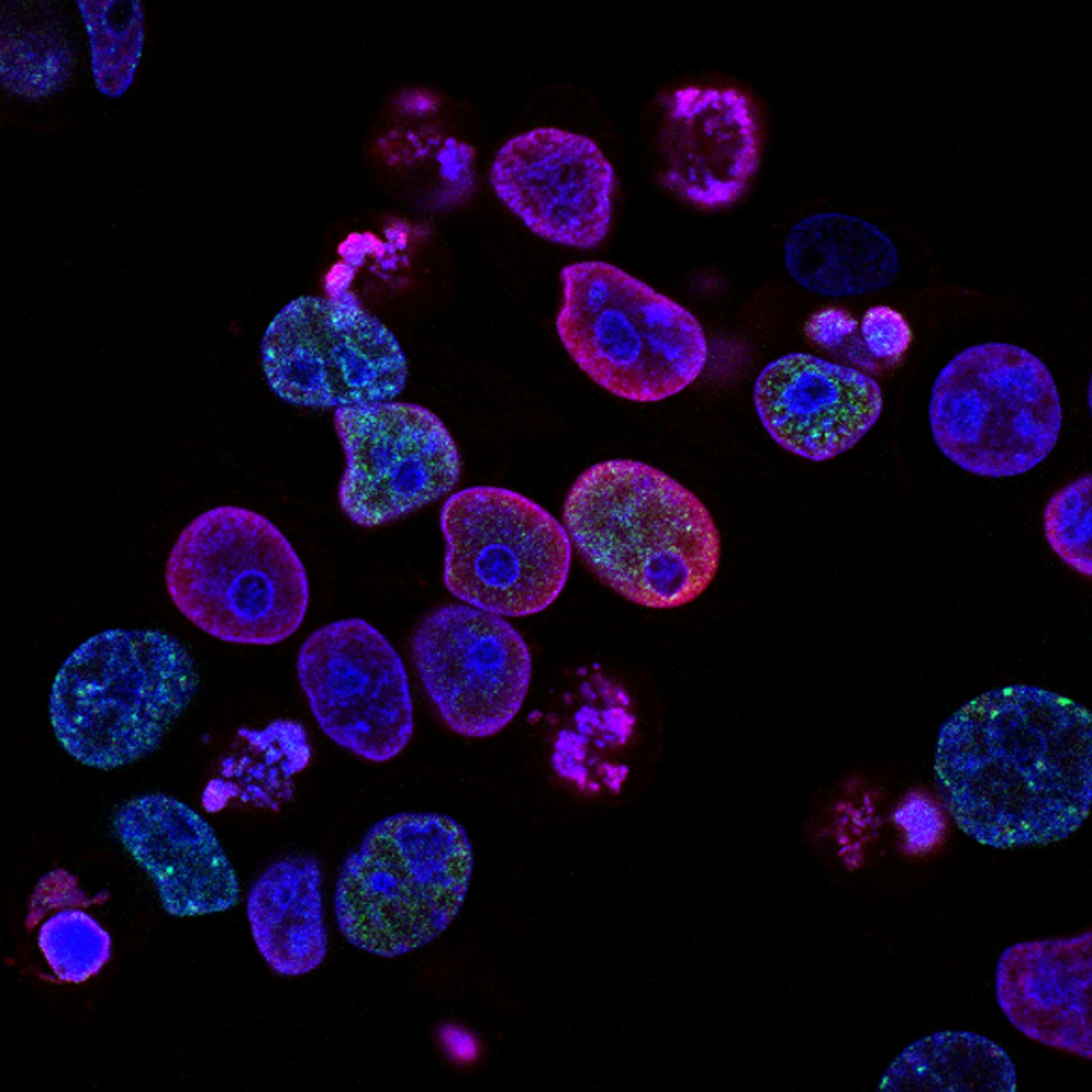

In their latest work, researchers Dr. Julia Majewska and Dr. Amit Agrawal discovered that senescent cells, much like cancer cells, overproduce the immune-suppressing protein PD-L1. This protein, commonly targeted in cancer treatments, prevents the immune system from recognizing and eliminating senescent cells.

The team traced this suppression to the p16 protein, a key component of cellular aging. As cells age, p16 levels rise, halting DNA replication and suppressing the breakdown of PD-L1. This dual mechanism—elevated p16 and unchecked PD-L1—creates an environment where senescent cells can thrive.

Beyond Aging: Broader Implications

Senescent cells aren’t limited to aging. Previous studies by Krizhanovsky’s lab linked their accumulation to chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), especially in smokers. The current research highlights how PD-L1 levels spike in both aging and COPD models. Human studies further confirm that COPD patients exhibit elevated p16 and PD-L1 levels, suggesting a common pathway.

Armed with these insights, the researchers hypothesized that existing cancer immunotherapy targeting PD-L1 could also eliminate senescent cells. Testing their approach in aging mice and those with lung inflammation, they observed promising results: immune activation, reduced senescent cell counts, and lower levels of inflammation-promoting proteins.

A Step Toward Targeted Aging Therapies

While this treatment doesn’t stop the aging process, it demonstrates a way to address the root causes of chronic inflammation and age-related diseases. Prof. Krizhanovsky notes that PD-L1 is not exclusive to senescent cells, making precision crucial for effective therapy. The team envisions engineering dual-target antibodies that recognize both PD-L1 and markers of cellular aging, creating more targeted and efficient treatments.

This breakthrough underscores the potential of immunotherapy to extend beyond cancer, offering new hope for addressing aging and chronic conditions.