In 1984, William Gibson’s Neuromancer delivered a groundbreaking vision of the future. Its opening line—”The sky was the perfect untroubled blue of a television screen, tuned to a dead channel”—set the tone for a dark, data-driven world ruled by technology, corporations, and inequality. This novel marked the birth of cyberpunk, a genre that rejected techno-utopian fantasies in favor of gritty realism and pessimism about humanity’s future under capitalism.

The Birth of a Genre: Technology Meets Dystopia

The 1980s saw the rise of personal computers, video games, and burgeoning corporate influence. Against this backdrop, Neuromancer introduced cyberspace and artificial intelligence as central themes, merging the allure of technological innovation with the grim realities of socioeconomic decay. Gibson’s protagonist, Case, is a washed-up hacker navigating a world where powerful corporations overshadow weak governments, AI evolves unchecked, and human life is commodified.

This “high-tech, low-life” dichotomy became the hallmark of cyberpunk. Massive, oppressive corporations control resources, while urban environments—dark, crowded, and chaotic—mirror the societal fallout of unfettered capitalism. The genre reflects the struggles of the marginalized: outcasts, rebels, and antiheroes caught in a world where progress benefits the few at the expense of the many.

Fredric Jameson, a cultural critic, famously described cyberpunk as “a new realism” that perfectly encapsulated the late capitalist condition. Works like Bruce Sterling’s Mirrorshades anthology (1986), Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), and Richard K. Morgan’s Altered Carbon (2002) expanded the genre, exploring themes like cybersecurity, urban decay, and the ethical dilemmas of advanced AI.

Cyberpunk’s Visual and Cultural Legacy

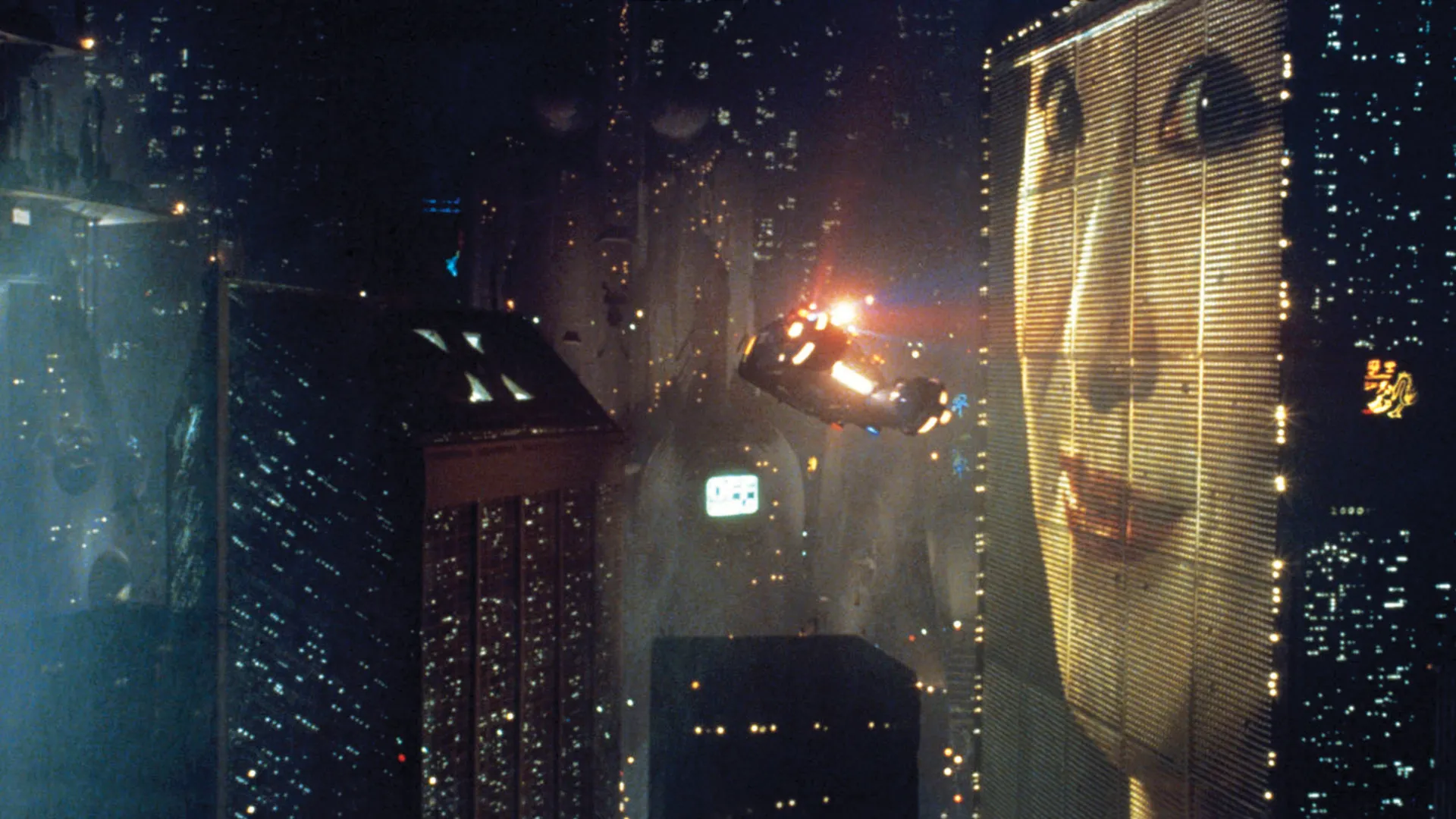

The genre’s aesthetic owes much to the noir tradition, blending shadowy, rain-soaked urban landscapes with neon lights, holograms, and cybernetic enhancements. This visual language found its ultimate expression in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), a precursor to cyberpunk that shaped its dystopian tone. While it lacks references to cyberspace, its portrayal of corporate-controlled cities and synthetic humans remains iconic.

Films like The Matrix (1999) and Ghost in the Shell (1995) advanced cyberpunk’s narrative and philosophical themes, questioning the nature of reality, humanity, and the costs of technological dependence. Video games such as Deus Ex and Cyberpunk 2077 expanded these ideas into immersive worlds, while the tabletop role-playing game Cyberpunk (1988) by Michael Pondsmith helped define the genre’s ethos.

Cyberpunk also fueled intellectual movements. Thinkers like Baudrillard and Mark Fisher drew parallels between the genre and real-world developments, such as hypercapitalism, urbanization, and human obsolescence. Federico Fernández Giordano called it “an accelerator of philosophy,” noting its ability to blend cultural critique with imaginative storytelling.

When Fiction Becomes Reality

Cyberpunk’s dystopian vision increasingly resembles the modern world. Corporate power often supersedes governmental influence, artificial intelligence grows rapidly, and social inequality deepens. Urban centers reflect the neon-lit chaos of fictional cyberpunk cities, teeming with globalization’s contradictions: sleek, high-tech spaces coexist with poverty-stricken neighborhoods.

In the 1980s, cyberpunk often looked to Japan as a symbol of technological progress, its influence evident in the genre’s aesthetic. Today, elements of cyberpunk are visible across global metropolises, from the tech-driven cities of Asia to the sprawling, chaotic urban centers of the developing world. Writer Luis Carlos Barragán observes, “The future is already here; it is just not equally distributed.”

A Genre for the Modern Era

Cyberpunk has always been more than entertainment. It critiques the systems shaping society, warning against the unchecked consequences of innovation. As the genre evolves, it continues to explore the intersection of humanity and technology, reminding us that progress is not inherently beneficial.

The genre’s enduring appeal lies in its relevance. In a world increasingly shaped by AI, data-driven surveillance, and climate change, cyberpunk challenges us to confront the systems we have created—and the futures they may bring. As the boundary between fiction and reality blurs, cyberpunk remains a vital lens for understanding our techno-capitalist age.